Likewise, I fully expected that after the champion three-year-old filly Blind Luck was defeated in her 2011 debut in the El Encino Stakes, cries of “bias” would fill the air like fireworks on the Fourth of July. Again, I was not disappointed.

“Speed bias helps Always a Princess foil Blind Luck in El Encino,” screamed Steve Anderson’s headline in the Daily Racing Form.

“My filly got beat,” said Jerry Hollendorfer, trainer of Blind Luck. “We may have to do something else. If the track stays the same way, I don’t think we’ll run here.”

So, what’s all the fuss about?

Well, for those not hip to the happenings at the Great Race Place — based on handle numbers, that’s the vast majority — speed has returned to the Arcadia, Cal. facility in a big way. Already, three track records have fallen by the wayside since the opening of the meet on Dec. 26 (including one that was held by the great Spectacular Bid) and every race seems to feature blazing fractions and early leaders that miraculously find a second wind down the stretch. According to Brisnet, 40 percent of the six-furlong races run at Santa Anita through Jan. 16 have been won in wire-to-wire fashion and the average winner is within 1.4 lengths of the lead at the first call.

Still, is that really proof of a track bias, one capable of stopping an Eclipse Award-winning filly and “The Sheets” Horse of the Year like Blind Luck? True, a 40 percent gate-to-wire win rate is exceedingly high for a non-bullring (track with a circumference of a mile or more). But it’s worth noting that, like Always a Princess, the majority of these “speed” winners have been well backed at the windows, suggesting that they possessed at least a modicum of past form.

True, a 40 percent gate-to-wire win rate is exceedingly high for a non-bullring (track with a circumference of a mile or more). But it’s worth noting that, like Always a Princess, the majority of these “speed” winners have been well backed at the windows, suggesting that they possessed at least a modicum of past form.

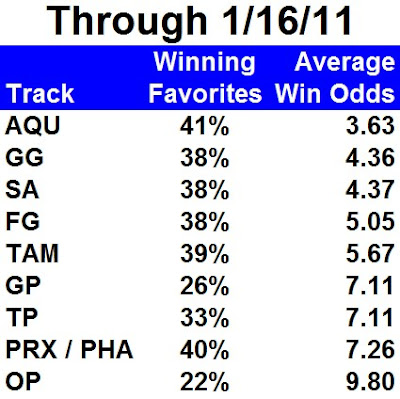

In fact, compared to other top tracks, specifically Aqueduct (AQU), Fair Grounds (FG), Golden Gate Fields (GG), Gulfstream Park (GP), Oaklawn Park (OP), Parx Racing (PRX), Tampa Bay Downs (TAM) and Turfway Park (TP), Santa Anita currently ranks third in terms of lowest average win mutuel. And while some of that is undoubtedly due to the less-than-robust field sizes in California (note that Golden Gate ranks second on the list), the low average odds are still meaningful given that smaller fields typically produce greater pace disparities (witness some of Zenyatta’s triumphs following sundial splits).

What’s more, if one ranks the tracks above based on the average winner’s trailing margin (if any) at the first call, an interesting picture emerges. In both sprints and routes, we see that Santa Anita plays second fiddle to Gulfstream Park, a venue that has traditionally been kind to early speedsters, but not one that has garnered blaring headlines and threats of trainer boycotts of late.

So what does all this mean? Well, I think it’s safe to say that Santa Anita’s new dirt surface is incredibly fast (at least so far). And I also think it’s safe to say that the surface, like most dirt surfaces, does, in fact, favor horses with good early lick — something that handicapping author Dr. William Quirin noted over 30 years ago when he called early speed the “universal track bias.”

So what does all this mean? Well, I think it’s safe to say that Santa Anita’s new dirt surface is incredibly fast (at least so far). And I also think it’s safe to say that the surface, like most dirt surfaces, does, in fact, favor horses with good early lick — something that handicapping author Dr. William Quirin noted over 30 years ago when he called early speed the “universal track bias.”

As for the track costing Blind Luck a victory in the El Encino? I don’t think so. In fact, if you watch that race carefully, you’ll see that Blind Luck was close — maybe too close — early, but fell back on the turn, as the leaders gradually began to pick up the tempo. Then, down the stretch she raced very erratically, while recording a career-low -18 late speed ration (LSR). Frankly, excepting ultra-quick frontrunners, a -18 LSR just isn’t going to cut it in a Grade I route and it makes me very dubious of this gal in her next start… whether she races at Santa Anita or not.

They recently added sand to the track, which might make it slower.

ReplyDeleteIn a world where racing insiders shape opinions, surprises are rare. Zenyatta’s Horse of the Year win felt predictable, akin to easily winning in Retro bowl . Just as the game's strategy requires skill, so does betting—creating fair odds is an art. The debate over Zenyatta's competition echoes the complexities of determining true value, illustrating that the race isn’t always to the swift but to the smartest.

ReplyDeleteSlope is a thrilling 3D racing game that tests players' reflexes.

ReplyDeleteNavigating life can feel like playing Drift Boss, constantly correcting for subtle biases we don't even realize are there. This inherent leaning, "The Bias That Isn't," pushes us off course. Unlike conscious prejudice, it's the invisible nudge influencing decisions. Successfully dodging this requires sharp awareness, just like mastering those hairpin turns in drift boss . Maintaining balance and staying on track demand continuous adjustment.

ReplyDelete